The First World War in the Netherlands

The First World War breaks out in the summer of 1914. During four years the war rages through the whole world, but the Netherlands are kept on the side: the country is spared the horrors of the trenches, of heavy bombardments, looting soldiers and villages without any men. This doesn’t mean the war goes by unnoticed. The Netherlands are faced with problems ensuing from neutrality, a flood of refugees, restrictions on the freedom of the press, mobilisation and shortages.

Striving for peace

28 August 1913

The Permanent Court of Arbitration, an international court of justice that encourages the resolution of disputes that involve states, takes seat in the Peace Palace in The Hague. The institute harmonizes with the Dutch effort for peace: the small country has every reason to advance peace and peaceful resolution on account of the overseas trade and its colonies. It has been choosing to remain neutral in conflicts for decades. Given the Hague Peace Conferences (1899, 1907), it seems logical to provide a home for the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

But the tensions in Europe are rising. There has been unrest in the Balkans for many years. The Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires are confronted with nationalist movements struggling for independent states or territorial expansion. In a few cases these movements are supported by Russia and sometimes they are combating one another. Two antagonistic power blocs are formed. An arms race develops and within a year of the official opening of the Peace Palace the major powers are at war.

Short documentary movie about World War One and the events leading up to the war. 1924. EYE Film Instituut Nederland, Production company: Universal (United States)

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie shortly before they were shot by the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip. Sarajevo, 28 June 1914. Photo Hollandse Hoogte/Corbis

International framework

Central Powers and Allies

The conflict is fought by two opposing power blocs. The Central Powers, consisting of Austria-Hungary, Germany, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, are at war with the Allies – amongst others France, the British Empire, Russia, Belgium, Serbia, who are joined by Italy and the United States. A number of countries have dominions and colonies. Therefore the war is not only fought on the Western and Eastern fronts in Europe, but also in Africa, the Middle-East and Asia. Soldiers from the colonies are fighting in Europe. In 1918 1.5 billion people from 33 countries are at war – about eighty percent of the world’s population.

A chain reaction

28 June 1914

Franz Ferdinand (1863-1914), heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie (1868-1914) visit Bosnia, a part of the Empire where there has been unrest for decades. An insurrectionary Serbian minority struggles for an independent Yugoslavian state or annexation by the neighbouring country of Serbia. A few members of a Serbian nationalist organization decide that the heir presumptive will not leave Sarajevo alive. After an unsuccessful bombing attack on the car of the royal couple, one of the members of the movement fires two shots using a pistol. Franz Ferdinand and Sophie die from their wounds.

Austria-Hungary issues an ultimatum to Serbia and declares war on 28 July. A chain reaction ensues. The international alliances, nationalist tensions and conflicts of interests all combine to breed naive expectations that plunge the European states into a war. The powder keg of Europe has exploded. The Great War has begun.

Cartoon on Dutch neutrality during World War One. A Dutch sailor is approached by a number of pretty ladies (the belligerent countries). Date unknown. Photo HH/Spaarnestad Photo

the Netherlands remain neutral

‘All we wish is to be left alone,’ the Dutch newspaper NRC writes on the first of August 1914. Holland’s position is clear: the country wishes to remain neutral. Neutrality is endangered by the Germans, who might plan to pass through the province of Limburg to invade Belgium and France. After a few days of war the Germans and the British indicate that they will respect the neutrality of the Netherlands, but only if this neutrality doesn’t benefit the enemy. Therefore the Dutch constantly need to compromise during the war so as not to offend one of both parties. Sometimes it’s a close call. In March 1916, for example, there are rumours that the British are planning to invade the country and in 1918 the Germans demand free transport across Limburg for the war effort.

International framework

Food and POW's

The Netherlands are not the only neutral country in Europa during the First World War. Other European countries who are not involved in the conflict are Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Spain and Switserland. This neutrality can be expedient for the belligerent countries. Prisoners of War are exchanged in the Netherlands. The country also supplies food, raw materials and financial services to both parties.

Mobilisation and boredom

1 August 1914

Fragment from the Leger en Vlootfilm (Movie about the Army and the Fleet) from 1917 by Willy Mullens. This was a propaganda movie about the Dutch army. Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid

International framework

Mata Hari, spie or innocent?

Large numbers of spies are active in the Netherlands during the First World War, especially in Rotterdam. English and German Intelligence Services also recruit Dutch citizens, who are able to cross national borders freely because of their neutral status. A few are exposed as (double) agents. The most famous spy was the Frisian Margaretha Zelle (1879-1917), an exotic dancer better known by the stage name Mata Hari. Supposedly she is an agent for both the Germans and the French. On 15 October 1915 she is executed by the French.

In order to prevent an invasion, the Dutch mobilise their army on the first of August 1914. Approximately 200.000 men join their barracks and are transported to the borders and the most important fortresses like the Waterlinie and the Defence Line of Amsterdam. The Netherlands make it clear that they cling to their neutrality and are prepared to defend it.

During the war years the soldiers of the Dutch army guard the borders and the camps that hold interned soldiers and civilian refugees. They try to stop smuggling and detect and arrest spies. The navy is in charge of the defense of the Dutch East Indies, coast patrol and minesweeping. But for lack of real acts of war the troops are soon getting bored, despite the continuing threat of war. Boredom is relieved by sports and educational programs. In the course of the war soldiers get permission to visit their wives and families more often and to return to their shop floors and fields.

Belgian refugees in the Dutch town of Bergen op Zoom accompanied by a nurse of the Red Cross (in the middle, with a muff). Photo Het Markiezenhof, Bergen op Zoom

One million Belgian refugees

10 October 1914

The battles begin in August 1914. The Germans invade Luxembourg and Belgium. They burn and loot the town of Leuven and conquer Antwerp on 10 October 1914. One million Belgians flee to the Netherlands, that have a population of only six million people. Local committees and private individuals spontaneously offer accommodation and help.

A large number of refugees returns during the war. Eighty thousand Belgians, both civilians and soldiers, eventually spend the four war years in the Netherlands. A lot of the civilian refugees are accommodated in ‘places of refuge’, small camps with facilities like a post office, an infirmary, a church, shops and even a library. The soldiers are disarmed and interned in camps. There are special camps for British and German soldiers.

Personal history

Bouncing boys carrying a bulging package

Not all commerce with Belgium is considered as smuggling; each person is allowed to take two kilograms of one product over the border. For a lot of Dutch families it provides a welcome addition to their income. The newspaper De Telegraaf describes a group of traffickers in August 1915: ‘Carts and wagons in all shapes and sizes, anything that has wheels, creaking and groaning under the weight of a load that is three times too heavy; hundreds and hundreds of cyclists with a package attached to their backs or to the frame of their bicycle, and thousands of pedestrians, men, women and children; children mostly! Bouncing boys and girls who all carry a bulging package when they enter Belgium and an empty bag when they come back.’

Refugee camp near Gouda, 1916. EYE Film Instituut Nederland, Production company: unknown.

International framework

The Wire

During the spring of 1915 the German occupier starts with the construction of ‘The Wire’, an electrified fence that carries 2,000 volts and runs for a length of about 180 miles along the Dutch-Belgian border. The ‘death wire’ has to prevent smuggling and espionage and stop men from occupied Belgium from passing through the Netherlands and Great-Britain to join the Belgian army, that is fighting against the Germans in the trenches near the Franco-Belgian border. From the end of 1914 the Western Front stretches from the Belgian North Sea coast to the Swiss frontier with France. This line remains essentially unchanged for most of the war, despite large-scale offensives and the use of poison gas.

A civilian is arrested by a customs officer. 1917. Photo Regionaal archief Nijmegen

Silver coins and brown bread

The first days of war produce widespread shock in the Netherlands. The Amsterdam stock exchange immediately closes after the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia. A large number of persons withdraw their savings and pubs only accept silver coins, that are stable in value. Monetary dealing are in a deadlock. The Dutch National Bank takes a number of measures to stabilise the economy: they forbid the exportation of gold and introduce emergency money to replace the hoarded silver coins, the ‘zilverbons’. Private persons take steps on their own initiative. Queen Wilhelmina (1880-1962) makes a personal contribution and donates money, wool and garments to a newly founded National Fund for the relief of destitute families.

Group portrait of the board of the Netherlands Overseas Trust in Amsterdam in the years 1914-1919 Painting by Antoon van Welie. Illustration Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The private ‘Netherlands Overseas Trust’, founded on 24 November 1914 by businessmen, bankers and ship owners, is particularly conducive to the stability of the country by entering into an agreement with the British, who are trying to ‘blockade the enemy to his knees’. Dutch importers agree to have their ships inspected and guarantee that the shipments are intended exclusively for the Dutch market. The system works reasonably well during the first two years of the war. All the majority of the Dutch population notices is that foodstuffs get more expensive. Sometimes they are compelled to settle for brown bread instead of the popular white bread.

Press and propaganda

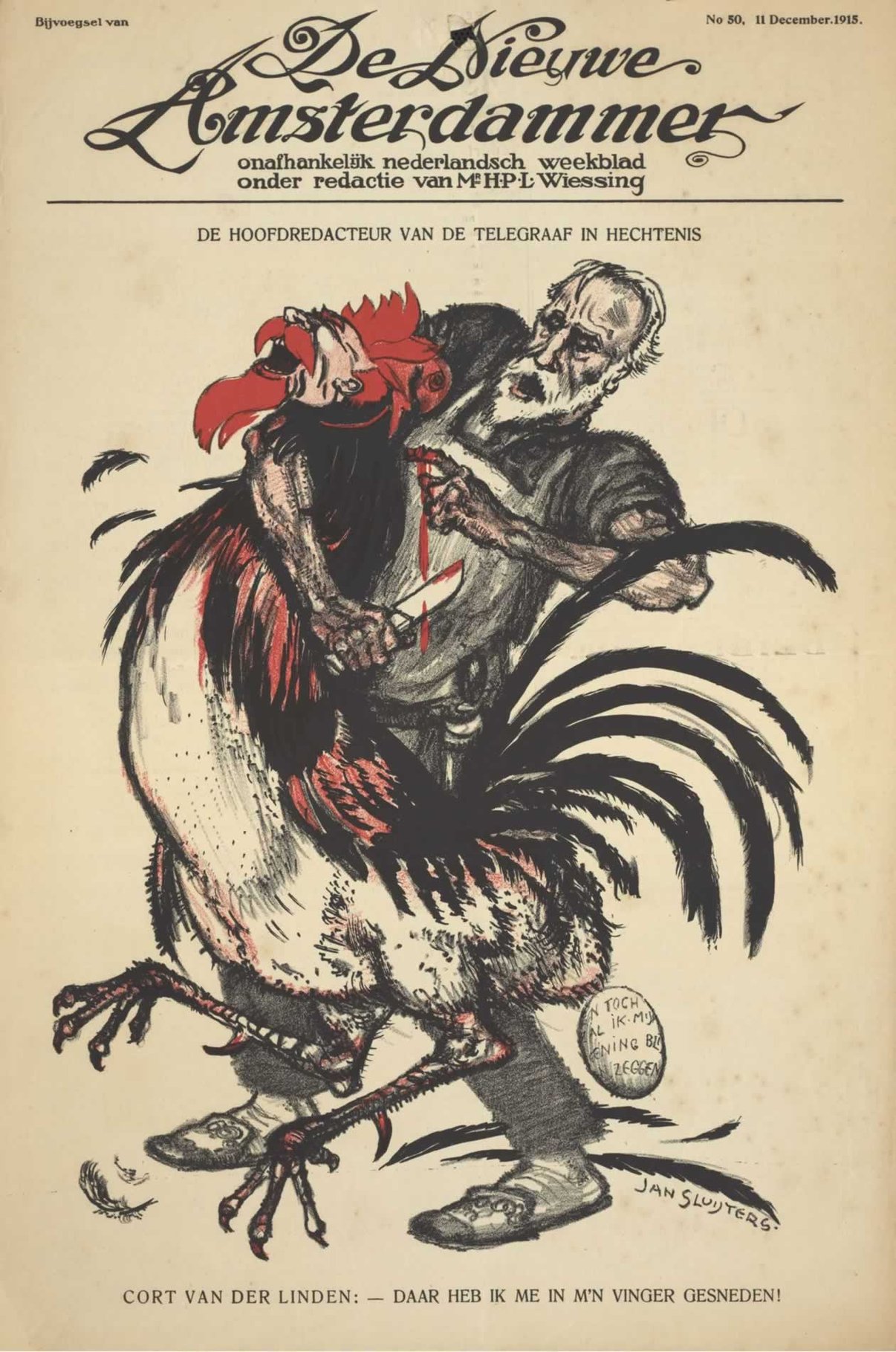

In Dutch homes the news on the war is followed attentively. Newspapers report extensively on the progress and consequences of The Great War. The Dutch government urges the press to observe a certain restraint: too much praise or too much criticism for one of the belligerent parties might endanger the fragile Dutch neutrality. Not everyone observes the requested reserve. Some newspapers and journalists are proponents of one of the factions and others are easily bribed.

But acts of war and war crimes do influence the public opinion. Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956), cartoonist for the anti-German newspaper De Telegraaf, is quite explicit about his ideas. The German emperor is portrayed as an ally of Satan, and the newspaper describes the Central Powers as ‘a band of heartless scoundrels who caused the war’. The editor-in-chief is arrested in December 1915 and released after seventeen days of imprisonment.

Photographs and movies often say more than words. In illustrated magazines like De Prins, De Katholieke Illustratie, Panorama and Het Leven a lot of space is reserved for illustrated reportages. And in cinemas the Dutch watch films and newsreels from England, France and Germany. These reportages are often partial, while the Dutch press is trying to remain neutral.

International framework

The virulent cartoons of Raemaekers

In his obituary in the New York Times cartoonist Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956) was remembered as ‘the one private individual who exercised a real and great influence on the course of the 1914-18 War.’ The first months of the war make a deep impression. After the German ravages in Belgium, he makes virulently anti-German cartoons. They are very successful in France and in the United Kingdom. A publishing company in London publishes a series of his cartoons, which gets translated in eighteen different languages. A lot of Allied soldiers bring his drawings to the front, in the form of small albums or cigarette cards. The Germans are not so pleased with his work. They try to force the Dutch government to place him on trial and in 1915 it is rumoured that they put a price on his head.

Cartoon from the magazine De Nieuwe Amsterdammer 'Editor-in-Chief of the Telegraaf taken into custody' Illustration BeeldbankWO2/NIOD

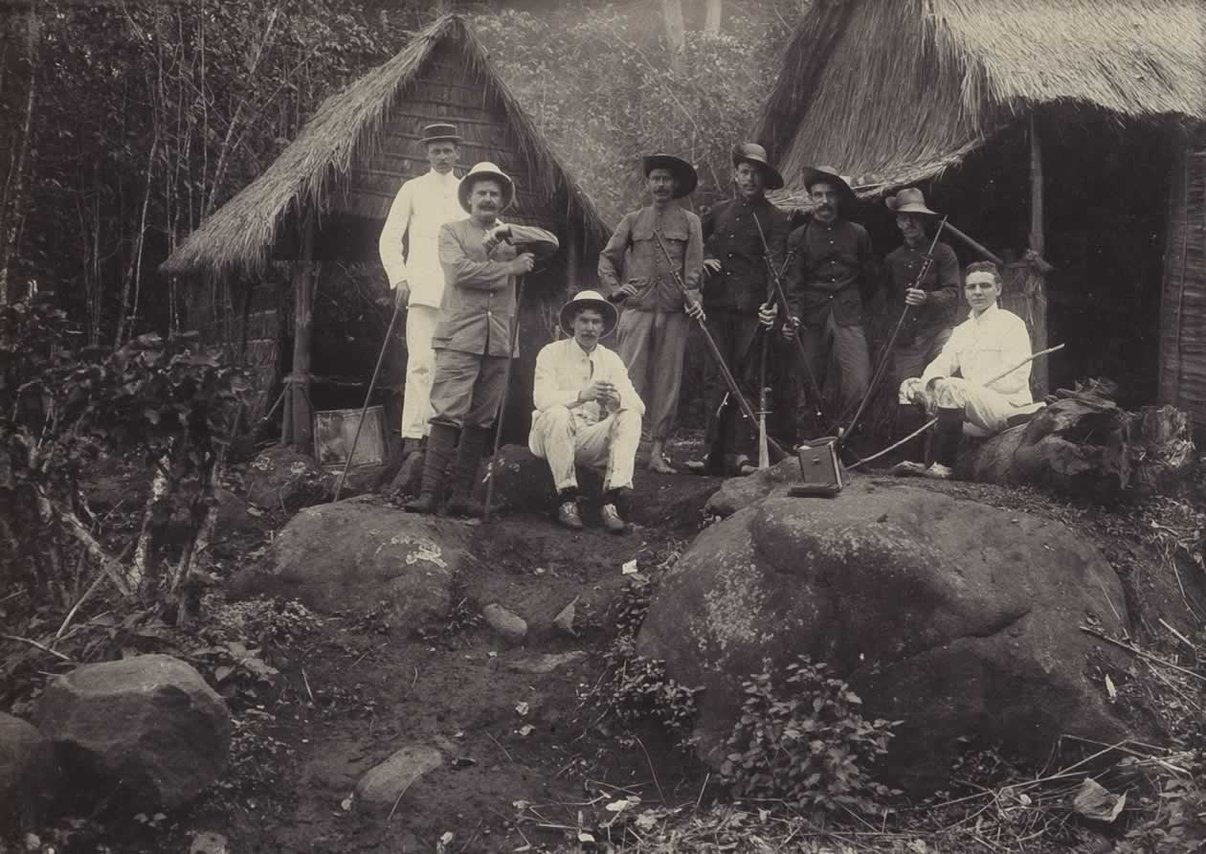

Shortages and unrest in the colonies

The Dutch Empire comprised Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles and the Dutch East Indies, Indonesia. The war makes it clear that the Netherlands heavily rely on other countries to keep in contact with the colonies. For instance, the British control postal and telegraph services with the Dutch East Indies and restrict imports and exports. Transport of passengers is getting more and more complicated, chiefly due to the German U-boats. The Indies no longer ship off their sugar, rice, oil, cotton, tobacco, tea and pepper to Europe and try selling them in their own region instead. Shortages in the Netherlands accrue. In the colony there are shortages of machines and medical equipment. In the last year of the war exports nearly come to a standstill. Famine and rebellion are imminent.

The commanding staff of the colonial army fear an invasion and are indecisive whether to train and arm the Javanese since they may rise in arms against the colonizer. Their fear is aggravated by the rise of the first nationalist organisations. The situation is different in the Caribbean West Indies, where restricted trade and communications are an incentive to small-scale agriculture.

Men, amongst others soldiers from the Royal Dutch Indian Army, probably in a bivouac in the Dutch East Indies. Around 1915. Photo KITLV

International framework

Double game by Lawrence of Arabia

Soon after the beginning of the war battles between the German and British colonial troops break out in Africa. From 1916 the Middle East also is an important scene for the theatre of war. The British Army officer T.E. Lawrence (1888-1935), known as Lawrence of Arabia, succeeds in organizing an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The British play a double game: they agree to honour Arab independence, but have secretly partitioned the Ottoman Empire with the French. This second plan gets carried out after the war. Just like the German colonies these territories become mandates; in fact they are geopolitical entities falling under European administration. France gets control of Syria and Lebanon, the British of Iraq and Transjordan. The British also make conflicting promises to the Arabs and the Jews, who wish to see an independent state established in Palestine.

International framework

Universal suffrage

The First World War is fought by men. The empty places they leave in the factories, on the fields and on the shop floors are usually taken by women. They keep the economy going now their husbands and sons are gone, sometimes never to return. But politically, women have no rights; in many countries the right to vote is restricted to male adults with a certain income and a certain level of education. The Great War brings changes. Universal suffrage is granted in the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom and the United States shortly before or after the end of the war.

Unanimity

The political consensus the Netherlands need to maintain their neutrality brings about a number of measures that are still perceptible today. For instance, a number of issues on private schools and universal suffrage (1917) is solved. The shortages show the importance of organizing the food supply. Partially in response to the flood of 1916 plans for closing the Zuiderzee finally pass parliament in 1918. Large areas of the Zuiderzee will be reclaimed for farming after the construction of the world-famous Afsluitdijk (1932), a large enclosing dam.

Construction of the Afsluitdijk. Around 1927. Photo Nieuwland Erfgoed

Soup kitchens and looting housewives

From 1917 onwards, the war is getting closer to the Netherlands. Increasingly, German U-boats and British minefields are an impediment to the merchant fleet and fishery. Since the Netherlands rely on imports from overseas, there is a shortage of important raw materials and, consequently, a decline in domestic production. There are great shortages and prices are rising. Corn is scarce. Compared to the previous year, potatoes are twice as expensive. Meat is getting rare. Rationing is introduced. During the last months of the war more than fifty products – fuel, onions, wood, metal, soap, garments, amongst others – can only be purchased with ration books.

International framework

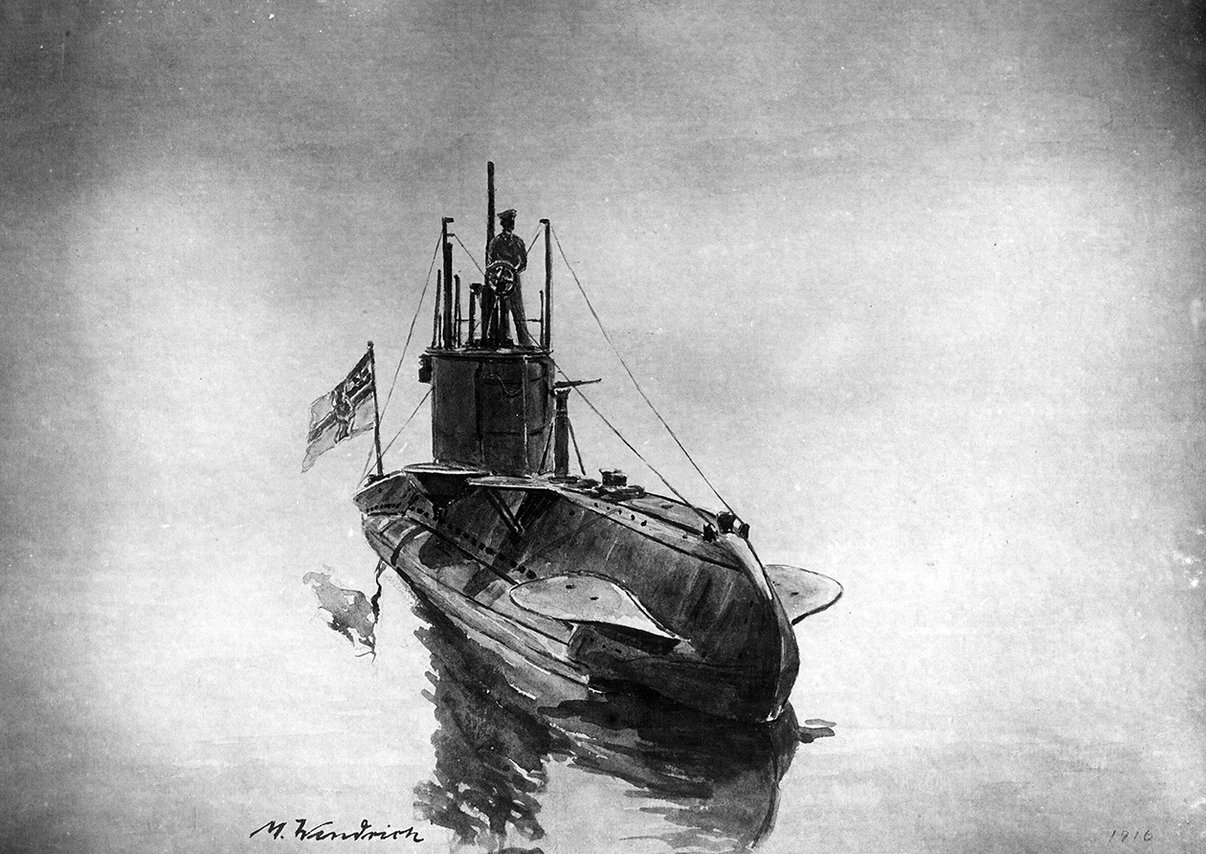

Submarine warfare and blockade

From February 1917 German U-boats sink all vessels approaching the British and French territorial waters. They try to force the British to surrender by cutting them off from the imports of fuel and raw materials on which they heavily rely. The regulations system set up in British harbours by the Netherlands Overseas Trust in 1914 is no longer functioning. A lot of fishing boats also suffer attacks from German submarines and it is now impossible to travel to the Dutch Indies through the Mediterranean. For the Americans this ‘Unrestricted Submarine warfare’ is the key reason to enter the conflict – they declare war on Germany in April 1917. The Dutch suffer consequences of this decision: the Americans decide to block exports of fodder, corn and fertilizer to the Netherlands. Furthermore they confiscate a large number of ship to transport their soldiers to the front in March 1918.

A German U-boat in 1918. Photo HH/Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo

The shortages call for inventive measures. Soup kitchens must provide cheap meals. School holidays are prolonged. Homes are cut from gas supplies from three to five hours each day. The popular allotments provide vegetables and people use balls of newspapers for heating instead of coal. The government tries to guarantee a basic food supply by introducing products like the ‘uniform sausage’ and the ‘popular biscuit’. The Dutch make the best of it and wait for better days.

Not everyone is obeying the law. A lot of farmers sell their crops on the black market or to the Germans, who are willing to pay much more. Furthermore the government is forced to sell potatoes, that are much in demand, in order to be able to procure fuel. The hungry population is dismayed and plunders food stocks. When Amsterdam housewives loot a freight of potatoes nine people are killed.

Three times as many millionaires

In the long term neutrality turns out to be good for the Dutch economy. Industry and commerce are given free rein on the national and international markets now that there is no foreign competition. Companies are forced to develop innovative activities that will turn out to be lucrative – Philips, for instance, will start blowing the glass for its light bulbs. Dutch mining experiences a rapid growth since German coal is no longer imported or only in very small quantities. The arms industry is developing and aviation is growing. At the end of the war the so-called war profiteers turn out to have become very rich, especially when compared to the rest of the population, that is suffering from the shortages. After the war there are three times as many millionaires as before the war.

Philips factory in Eindhoven. Eindhoven, 1915. Photo Regionaal Historisch Centrum Eindhoven

International framework

Breakthrough for aviation

The First World War is the first war in which aviation plays a significant role. Zeppelins and aeroplanes, sometimes produced by Dutchman Anthony Fokker (1890-1939), are used for aerial warfare and for bombing. Dutch airspace is often violated by the British and the Germans. For lack of any anti-aircraft defence there is not much the Dutch can do. The Netherlands are also accidentally bombed on several occasions. But the First World War is not only a breakthrough for aviation, but also for technological innovations such as tanks, machine guns and poison gas.

International framework

Revolution in Europe

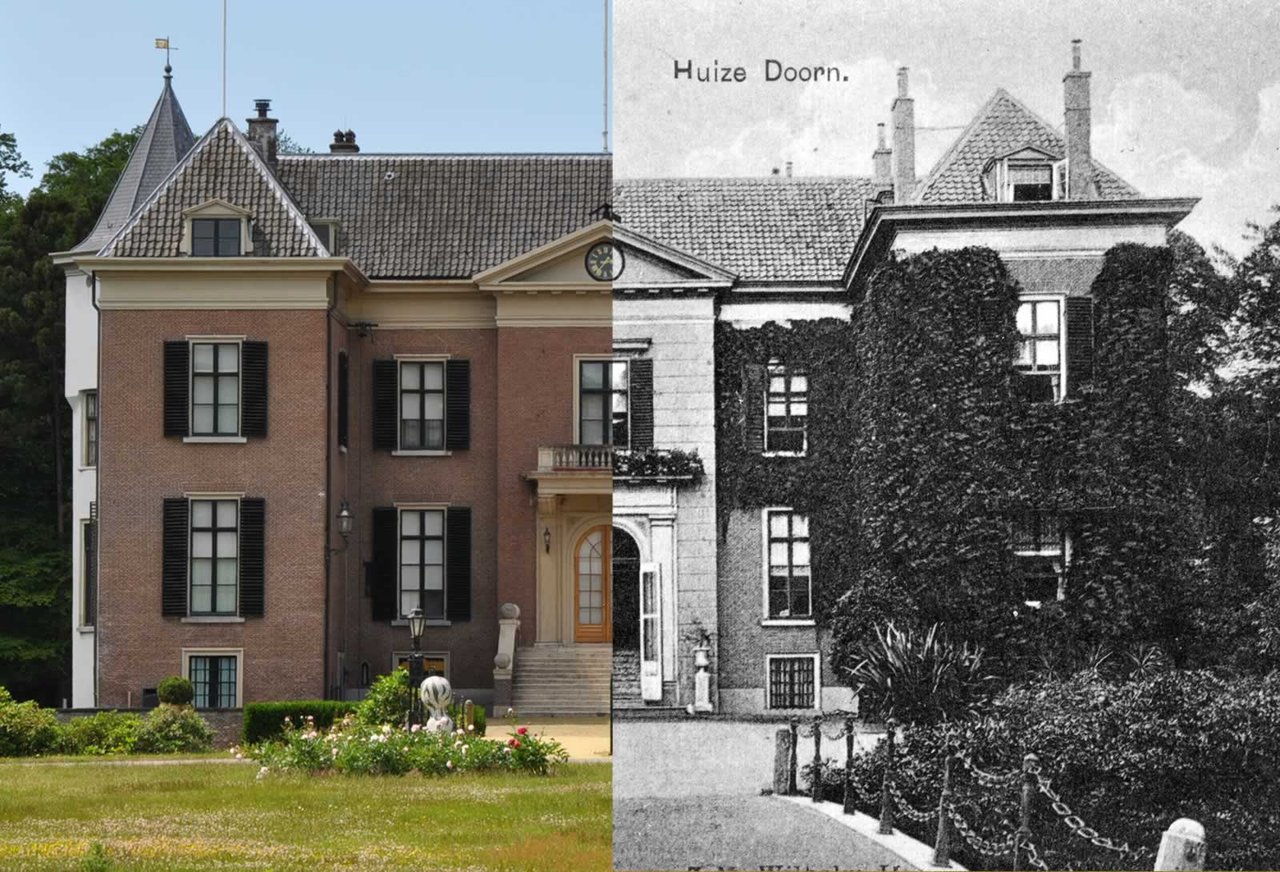

In 1917 the tsarist autocracy is dismantled during the Russian Revolution and replaced with a communist government. The new regime ends Russian participation in the First World War after a few months. A revolution also takes place in Germany in the fall of 1918. The emperor is forced to abdicate. He flees to exile in the Netherlands, where he will end his days in Huis Doorn. The end of the war also means the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires. Towards the end of the war a revolution also seems to be taking place in the Netherlands; soldiers are threatening to rise in rebellion and people are hungry. The socialist leader P.J. Troelstra (1860-1930) calls for a revolution, but is soon compelled to admit that he was mistaken.

An English cemetery at the front. 1917. Photo HH/Roger-Viollet

Nine million soldiers lost

11 November 1918

Towards the end of the summer of 1918 it becomes clear the Allies will win the war. Germany is war-weary and has its own trouble with a revolution. The country agrees to an Armistice on 11 November 1918. Peace negotiations start immediately. The war may be over, but continues to reverberate. The First World War has taken away a whole generation; nine million soldiers have died and a lot of survivors suffer physical and emotional wounds from which they will never recover.

French president Georges Clemenceau speaking during the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. American president Woodrow Wilson is on his right. Versailles, 1919. Photo HH/Corbis

Winners and losers

28 June 1919

The map of Europe is redrawn in the Treaty of Versailles – signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand – and in other peace treaties at the end of the First World War. The Allies demand territorial concessions and reparations for all the loss and damage during the war. An international organisation, the League of Nations, now has to deal with settling international disputes through negotiation. It cannot prevent another devastating war from breaking out twenty years later. The neutral kingdom of the Netherlands will not be spared this time.

Commemoration and memory

The Menin Gate in Ieper, where the Last Post is sounded every night.

The First World War lives on in memory as the senseless slaughter in the trenches on the western front. This is the aspect that always gets most attention in movies, stories and poems about the Great War. But the soldiers have probably not experienced it as senseless. They persist, fight for their country and try to force a breakthrough. Furthermore the First World War was much more than just senseless slaughter in the trenches. The conflict had the effect of bringing new social relations and technological innovations – also in the Netherlands.

Because of the neutral status of the Netherlands, most Dutch war victims were seamen and fishermen. As a consequence the First World War doesn’t get paid the same attention in the Netherlands as in the surrounding countries. But with the Centenary Commemorations Dutch people seem to be taking an interest in the Great war. They visit the battle fields, museums and places of remembrance like Huis Doorn, where the German emperor sought refuge after the war.